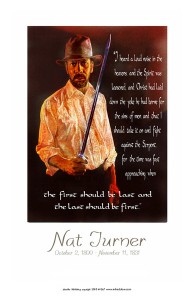

The Confessions of Nat Turner, The Leader of the Late Insurrection in South Hampton, VA.

Nat Turner Rebellion

Perhaps no other moment in history crystallized the fears of slave owners in the South like the 1831 slave insurrection led by Nat Turner in South Hampton, Virginia. During a span of approximately thirty-six hours, on August 21-22, a band of slaves murdered over 50 unsuspecting whites (Goldman). The exact number of whites killed remains unsubstantiated—various sources claim anywhere from 50 to 65. Almost all of those involved (or suspected of involvement) in the insurrection were put to death, including Nat Turner, who was the last known conspirator to be captured. Following his discovery, capture, and arrest over two months after the revolt, Turner was interviewed in his jail cell by Thomas Ruffin Gray, a wealthy South Hampton lawyer and slave owner (French). The resulting extended essay (summarized below), “The Confessions of Nat Turner, The Leader of the Late Insurrection in South Hampton, VA.,” was used against Turner during his trial. The repercussions of the rebellion in the South were severe: many slaves who had no involvement in the rebellion were murdered out of suspicion or revenge.

Perhaps no other moment in history crystallized the fears of slave owners in the South like the 1831 slave insurrection led by Nat Turner in South Hampton, Virginia. During a span of approximately thirty-six hours, on August 21-22, a band of slaves murdered over 50 unsuspecting whites (Goldman). The exact number of whites killed remains unsubstantiated—various sources claim anywhere from 50 to 65. Almost all of those involved (or suspected of involvement) in the insurrection were put to death, including Nat Turner, who was the last known conspirator to be captured. Following his discovery, capture, and arrest over two months after the revolt, Turner was interviewed in his jail cell by Thomas Ruffin Gray, a wealthy South Hampton lawyer and slave owner (French). The resulting extended essay (summarized below), “The Confessions of Nat Turner, The Leader of the Late Insurrection in South Hampton, VA.,” was used against Turner during his trial. The repercussions of the rebellion in the South were severe: many slaves who had no involvement in the rebellion were murdered out of suspicion or revenge.

William Styron’s The Confessions of Nat Turner appeared in October 1967 and won the Pulitzer Prize in fiction in 1968. The novel is based on the true story of a violent slave rebellion in Virginia in 1831, led by a divinely inspired preacher and slave, Nat Turner, whose actual jail-cell “confession” had long been part of the historical record.

William Styron’s The Confessions of Nat Turner appeared in October 1967 and won the Pulitzer Prize in fiction in 1968. The novel is based on the true story of a violent slave rebellion in Virginia in 1831, led by a divinely inspired preacher and slave, Nat Turner, whose actual jail-cell “confession” had long been part of the historical record.

With its excruciating violence and its merciless depictions of the degradations and humiliations of slavery, Confessions proved to be as much an “event” as it was a work of literature. It was no doubt the first experience that millions of readers had had with the sickening stories of America’s “peculiar institution.” Surely no history book had ever provided such a visceral narrative, and popular fiction had also steered clear of slavery, with a few notable exceptions, such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published more than 125 years earlier.

Styron’s novel attracted at first the praise of mainstream white critics as well as that of some black writers, notably James Baldwin (a personal friend of Styron’s) and Ralph Ellison, author of Invisible Man. Baldwin wrote of Styron: “He has begun the common history–ours.”

But the good will began to unravel in the summer of 1968, with the publication of William Styron’s Nat Turner: Ten Black Writers Respond, a collection of essays by black historians and other intellectuals. The writers attacked Styron for what they deemed historical inaccuracy and “a vile racist imagination,” but most were simply outraged at the presumptuousness: that a white writer could dare to write so intimately of the black experience. In one of the most measured of the essays, historian (and associate of Dr. King) Vincent Harding takes issue, strongly, with Baldwin’s claim about Styron’s writing “our common history.”

Harding writes:

Surely it is nothing of the kind. Styron has done nothing less (and nothing more) than create another chapter in our long and common agony. He has done it because we have allowed it, and we who are black must be men enough to admit that bitter fact. There can be no common history until we have first fleshed out the lineaments of our own, for no one else can speak out of the bittersweet bowels of our blackness. Only then will we capture Nat Turner from the hands of those who seem to think that entrance into black skin is achieved as easily as Styron-Turner’s penetration of invisible white flesh.